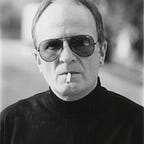

A.W. Hill, Author of Ministry (TouchPoint Press)

He nearly tripped over the body, making his way chin down against the wind to Podwale, the only bar in the Warsaw Old Town open on Christmas Eve. It was cold, colder than normal even for Poland, and his first thought was that the person wrapped in a tattered blanket might no longer be alive. When the toe of his boot had struck what seemed to be a ribcage, it had been stopped hard, as if the organs were frozen solid, and no moan had come. The poor, the poor, he thought. Damnit, they really were at the heart of the matter of Christmas. If you’d been raised more or less Christian, and whether you were observant or lapsed, the ragged poor became suddenly more visible at this time of year. They did if your notion of Christmas had been shaped by Dickens and St. Luke, as it had been for him. Oh yes, he’d loved the presents and the music and the glow of colored bulbs, but even as a young boy, lying beneath the boughs of the Christmas tree and gazing up into the galaxy of incandescent red, green and blue, he’d seen in his mind’s eye only the family in the cattle shed, the babe on the straw. Why this was, he couldn’t say. His parents hadn’t been especially religious, and but for the scented candles and the strains of Good King Wenceslas coming from the phonograph, Christmas hadn’t been an especially solemn affair in his home. Later, when he’d become a young man, it had been mostly about booze and hoping to get laid by a local girl when you came home from college. Nonetheless, the onset of Yuletide had always brought with it an ache in the breast that said he ought to be ‘keeping Christmas’ better. That he had been in some vague, undefineable way, remiss.

None of this at first gave him pause as he side-stepped around the body and made the usual rationalizations for his callousness: the stinking, desperate, infectious poor were to be gotten away from as quickly as possible. Moreover, they had probably brought this fate upon themselves — alcoholism, drug addiction, depravity. Still, he stopped a few yards on and turned to look at the body from a different angle. A pang of guilt, probably, and the momentary thought of the person he should have been, rather than the one he was. He walked slowly back, coming close enough to smell the zoo odors rising from the filthy blanket, the smell of underpasses streaming with urine, or of a homeless man who steps into a New York subway car while everyone turns away and pulls their scarves up over their noses. He stooped slightly over and said meekly, “Are you okay?” though he knew that his English would not be understood, and knew also the Polish expression for the same: nic ci nie jest? The truth was he hadn’t wanted to hear an answer. He’d just wanted to ask the question before he went on.

Still, he felt for a vanishing moment like a saint for even asking. There was no answer, but almost immediately, he was reminded of why no one ever stops. If you stop, something will be asked of you, even if only the sacrifice of time. You will have stepped into a circle, acknowledged your connection to another human soul, allowed it to pull you in and down, and who knew if you’d be able to extricate yourself. The blanket moved, and from beneath it came a bony, outstretched hand. The skin was so chapped and broken and brown with grime that it was impossible to tell its age, and so emaciated that it might have been either man or woman. He fished into the deep pocket of his long woolen coat for the wad of Polish bills that constituted his drinking money for the evening, and put into the trembling palm a ten zloty note. Then, before the fingers could close, he added another. Enough money for a sausage and sauerkraut from a street stand. If it wasn’t used for alcohol.

He turned quickly away and moved on, and once again, he felt absolved. He’d done a good thing, been a decent person. Now he could meet his friends, drink and laugh without guilt. But he was still captive of the circle and the words came again: the poor, the poor. The poor, the poor, the wretched poor, are not separable. As he walked on, the words took on a voice. His voice, but of another world, another reality, the small boy lying beneath the boughs. What do you do with this, he asked. Do you go home and hastily donate your drinking money to a local food bank? Would that buy absolution? For a day, perhaps. Do you found an online charity? Such things were easily done these days. Build a website, ask for money, and money would flow. Or do you trade your street clothes for sackcloth and enter a monastery? He had a tendency to obsess once these demons of thought had invaded his mind, and suddenly the weight of the world’s suffering was on him. The words came back with a new voice asking, what would you give if that gift would lift the world’s poor out of poverty? If an angel instructed you to do so, would you give your life? With the bar in sight, he ducked into an alcove to be free of the wind and considered this. If that deal could be sealed, then yes, in principle. He was still a youngish man, but he’d had a life rich in experience and relative comfort. If a bus were to hit him, his last thoughts as he lay in the street, blood draining from his body, would not be “but I really wanted to see Thailand.”

The bar was crowded and the customers were boisterous. Now at last he was cleansed, because, in principle, he’d agreed to give it all up. Now he could drink with Roland, who also taught at the conservatory, and flirt with Margot, who he’d had his eye on all semester, but about whom, given the strange, bound and gagged nature of sexual politics in this era, he couldn’t say gay or straight with certainty. Maybe tonight he’d find out. Three expats in Poland, conjuring the Christmas spirit with gin. He was on his third when the nausea hit him, and thinking he might’ve eaten some undercooked pork earlier in the day and might be about to vomit, he excused himself to go to the bathroom.

Gripping the washbasin, he raised his eyes to the mirror to see if he had gone pale. His hair was damp and his forehead beaded with sweat. He bent over and tried to vomit, but all he could do was retch. When his head came up again, the angel was there. It was not as he might have thought. No winged seraphim with golden curls. It was the absence of him and the presence of another, multiplied by an infinite hall of mirrors. He felt a kind of bliss, and laughed for an instant, thinking so these must be the ‘better angels’ I’ve heard so much about. The words came back: the poor, the poor, the wretched, ragged poor. “Okay,” he said softly. “Okay.” It was because he had stepped into the circle of souls, because he had allowed himself to feel one with another. “I’m going to miss it,” he said aloud, “but it’s okay.”

And then he was no more.

On Christmas morning, the bells of St. John’s Archcathedral rang out. It was, from the perspective of our plane of being, a very different kind of Christmas, but no one there knew this, or knew who deserved the credit for making it so. It had always been so. Thus does a single choice make a new world, and the child is born again under the star of David.