THE WISE MAN:

On Balthazar’s nineteenth Christmas Eve, when he was still living at home, a basket had been left at his door with a note pinned to the top. It was a lidded picnic basket of the old-fashioned kind, rescued from some garage. He’d noticed that the basket was twitching slightly, and had immediately thought of a puppy, or maybe something wild put there as a prank. His family was poor, so the church did sometimes leave food at Christmas, but they would not, he thought, have left anything that needed to be fed.

He opened the note before looking in the basket. In a shaky feminine hand, it read, “Trust me. It’s yours.”

Balthazar had raised the baby girl, whom he called Eve after the occasion of her delivery, with generous help from his mother and maternal grandmother. He’d been wary at first, and wholly unready to be a parent, but his mother had said that despite the sins of the baby’s mom, whoever she might be, the child’s soul was spotless, and caring for it could only bring grace to the family. It did not take long for Balthazar to love Eve, and as he stood at dusk on the front stoop on which she’d been laid, cradling and rocking her, he would coo and sing, “You’re spotless. You’re pure. You’re the one true thing.”

Years passed in a happiness as tenuous as a held breath. They never had enough money, but they were a pack, and they watched over each other. Eve grew up, and when she was fourteen and had finally come to resemble her mother, Balthazar did something to earn his daughter’s hatred, if not God’s eternal wrath. There’s no point now in reliving the incident, for there’s no grace to be gotten from recrimination, especially when all involved are now dead. It had happened just once, but once is enough for a lifetime. Eve ran away, and found a life on the margins of the world that was as bleak as her mother’s had been, and Balthazar knew that whatever harm came to her was his doing because he had forgotten in that one moment of brute, ancestral reflex that she was spotless. He prayed every day for forgiveness, but Eve did not return or forgive him, and it was only her forgiveness that mattered.

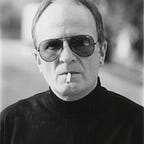

It wasn’t until Eve was thirty and Balthazar forty-nine that he learned of her whereabouts. By this time, he had gone from his mother’s house to a mini-trailer in South Pekin to the backroom of the gas station where he worked and got what redemption he could from repairing axles and what relief he could from pills. He’d seen his mother through eight years of cancer and did his part for the local YMCA, but he never set foot in the church after what happened, and he knew no amount of good deeds would square things. When he got her address, though, he found a jolt of purpose, and for a while, made real efforts to connect. She evaded every attempt. When enmity is that deep, it finds its ways.

Finally he gave up, and no sooner than he did, his mother died. The grief pulled him away from his mission, and Eve, downriver a hundred miles, slipped deeper into Mississippi sludge: the whole range of things you have to do when you have a habit and no money to feed it. When Balthazar next had word of her, it was from the State Police. She was in a mandatory rehab facility and sick with some kind of STD. On the day he learned this, he also learned that his mother, who had been secretly hoarding, holding out for thirty years and investing in gold, had left it all to him: just under eighty-thousand dollars worth at current prices. That was November 30. In two weeks, the account was in his name and he knew what had to be done with it.

Balthazar used the gas station’s old computer at night to search for the things he needed to know. You can find instructions for doing almost anything on the internet. What Balthazar needed was instructions for making a last will and testament that didn’t need a lawyer, and secondly, for how to put the little gold brick safely in Eve’s hands after his death. He’d put no restrictions on her use of it. He arranged everything — the insurance, the secure transport to where she was being kept, its delivery on Christmas Eve in the same picnic basket she had come in. And of course, the note, which said simply:

“I don’t believe that what I did can ever be forgiven on earth, so I’m hoping for another place. I want you to be well. I want you to find something to take care of, something little and helpless that just pulls all the love out of you. I never felt so well as when I was taking care of you. You’re spotless and pure, and you’re my one true thing. The shadow’s gone now. Live.”

When it had all been taken care of and the package was on its way, Balthazar attached the hose to the exhaust of the old Buick he’d been working on, drew the other end into the car with him, rolled up the windows and turned the ignition. He listened to Christmas music on the car radio. Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town. Holly Jolly Christmas. I’ll Be Home For Christmas. And somewhere before the final refrain of The First Noel, he died.

Eve came back to the town she’d been raised in. She had his body exhumed from the public graveyard out near the interstate, properly laid in a fine, brass casket, and put down in the churchyard beneath a sycamore tree with a headstone that said, ‘Loving Father.’ The truth was, she said to herself, she’d forgiven him long before, but by that time there was too much scar tissue around her heart. The wound was sealed over, and forgiveness meant opening it up. But with his willing death, he had relieved her of that wound-opening, and given her back the ability to love. She married a veterninarian who’d fallen for her as she drew his beer at the Pekinese Pub, and never after lacked for little, helpless things to care for. To anyone who asked, she’d say, “My father was a good man. He saved my life twice at Christmas. He brought gold to the manger.” She never troubled to explain the last part but no one asked until years later, when on the anniversary of her father’s death she stood at his gravesite with the pastor of her church, the same one her father had left.

“Who do you think God loves most?” she asked him. “The sinner who tries to make up for it or the one who never sins at all?”

“I think God favors the one who comes with with his sins held in open hands,” the pastor replied. “Whether or not he’s been able to atone for them.” And he added: “Just as your father came to your manger with the gold in his hands.”